John emailed to ask:

As I understand it, the layering of graphite is a major part in order to achieve the desired effect of tone and texture. But what I cannot understand is, after reading somewhere that it is almost impossible to build up tone from light to dark and that it must be done from dark to light, I believe it has something to do with hard graphite filling in the hollows of the tooth and then preventing softer grades from staying on the paper. Is this understanding somewhere near the mark, or I am totally way off the mark?

As with all things in Art there are no rules, which means I agree with your understanding and observation but I also know excellent artists who work light to dark. Personally, I belong to the dark to light camp, and here’s why…

First, you must understand the properties of graphite and the manufacture of pencils.

The crystalline structure of graphite is layers of flat plates. That’s why graphite reflects light while the irregular grains of charcoal and carbon don’t, and why graphite is an excellent dry lubricant. It also helps to explain why erasers are usually ineffectual at removing graphite – because once the erasing surface becomes graphite coated it simply slides plates over plates.

Raw graphite produces a black mark. In order to create differing grades – degree of hardness or softness – the graphite is mixed with clay. Imagine that an 8B is almost pure graphite and an 8H contains mainly clay and little graphite. Clay does not possess the plate-like structure of graphite, so the flat-plate structure is diluted as the clay content increases and the grades become harder.

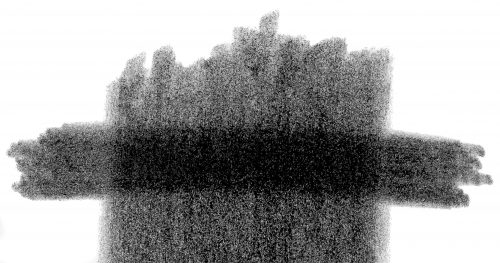

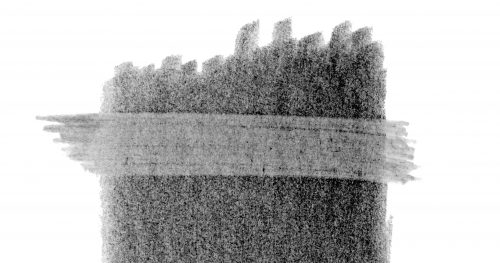

The more clay added to the mix, the harder the grade and the lighter the achievable tones. For example, 6B has a far greater graphite content than 6H, which contains much more clay. This means 6H has a very fine composition and draws smoothly and light, but the softer 6B draws darker with a much grainier appearance.

Of course, this is a general description. In reality, the process varies between manufacturers and the quality they set out to achieve. A manufacturer of cheap pencils, apart from using inferior graphite, might also use inferior clays, which may be ground for less time – possibly just a few hours instead of days. Personally, I use Staedtler leads that are wonderfully consistent and impurities are almost never encountered.

There are more variables to consider too. For example, papers differ greatly, so what works on my ultra-smooth Conqueror Diamond White might not work on a more textured paper, and vice versa. It’s the tooth (the pits and crests in the paper’s surface) that causes the graphite to flake off the pencil’s lead, and some papers possess much more tooth than others.

If you use a soft grade (B to 8B) its minimal clay content means the individual graphite grains are large and won’t fill the pits of the tooth entirely. This leaves flecks of white paper showing through it, but that can be solved by burnishing with a harder grade – HB over 2B, for example – so the harder grade breaks up the softer one and fills the remaining tooth.

Because the soft grades always leave some tooth unfilled, you can always layer a hard grade over a soft one.

Conversely, hard grades (H to 8H) fill the tooth completely with a mix of clay and fine graphite particles, leaving insufficient tooth to accept the soft grades. Their large flat plates simply slide over the top and won’t hold. Remember, graphite is a dry lubricant, so it’s simply doing what it knows best. You can feel this in use, as the soft grade skates effortlessly over the harder grade. It’s much harder to get that soft graphite to stick to the harder underlying layer, and often impossible.

TURNING DRAWBACKS INTO BENEFITS

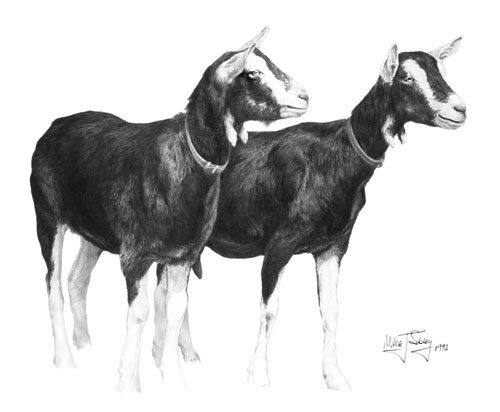

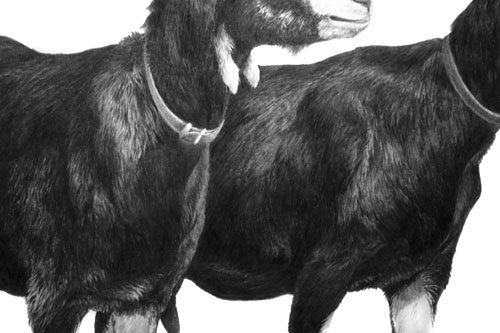

There is a technique that I’ve sometimes used that turns this problem into a benefit. You can create your own “masks” – like acid resist in etching. It works best in areas of high contrast, such as highlights on hairs within a black coat. Simply draw your highlights first, with a 4H or harder grade applied with some weight, and then apply a layer of soft grade over it, perhaps 2B or 6B. As the soft grade slides over the lines of hard grade, those lines turn from visible, comparatively dark lines into light highlights. It gives quick results but is not entirely controllable.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DARKS

Personally, I feel the often-taught method of building up dark values from a lighter base is simply an admission that no firm decision has been made about the value required. Instead, I advocate the immediate application of the desired value. It produces the freshest drawing and, because it requires a confident approach, the result is sharp and clear. And, perhaps more importantly, as soon as the darkest value is established in a drawing, the entire palette of available greys is known and all midtones automatically fall into place.

I know I often repeat myself when promoting the use of dense and solid blacks and darks but they really are important. It’s light and shadow that make a drawing, not middle values. If you want your subjects to appear three dimensional, you must have light and shade. Look at the drawings of Ingres or the paintings of Rembrandt for clear lights and darks. And if you work from photographic references, try to find high contrast ones and not ones with almost all middle values – although with practice you should be able to interpret mid-value photos as though they were high contrast.

When someone looks at your drawing their brain will register the darkest value, however small, and then read the white of your paper as being pure white. From those check points it will compare the two extremes and understand all the mid values. The wider the overall tonal range the more three-dimensional information you can impart.

FINALLY…

When you’ve completed your drawing, or a completed section of it, lightly shade with a 2H, or 4H, over everything, avoiding only the highlights. That will remove all non-intentional white from your drawing and your highlights will shine with an increased brilliance.