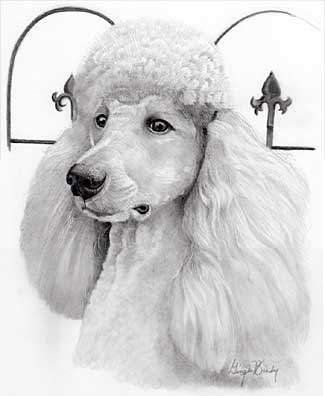

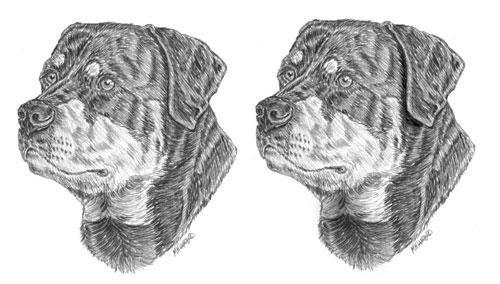

Artist Ginger Brady emailed me to ask:

I am wondering if you get asked by many people if you would do your drawings in color instead of Black & White? I am having many folks tell me they would buy my work “if only” they were in color or had some color to them? Have people asked you to add color? I have, to appease a few people, but I am not happy with the results from colored pencil or water color. I miss my Graphite pictures and I feel like I’ve been wasting a lot of time trying to make others happy.

Been there, done that, Ginger. And like you, I found that “working for others” didn’t appeal. I had to stay with the medium I really care for and working for “me”. That’s what art is about, isn’t it? Expressing your love or feelings for something. Displaying the subject to your viewers and saying “Look at this. No, look closer. See what a beautiful creation this is.” To my mind, there’s a world of difference between “fine art” and “illustration”. The first involves passion and is personal, the other is commercial and mechanical. I suspect your “must work in colour” art is creeping into the latter category.

It’s been said that “Colour appeals to the senses and drawing appeals to the mind”.

For me, colour gets in the way; it’s a distraction. Colour allows the eye to quickly pass over an image and gather enough information to be satisfied. A brown horse in a green field can be identified in a nanosecond and possibly dismissed. Remove the colour and the mind has to linger to gain an understanding. And in that time span, however short, we graphite artists have the chance to grab the viewer’s attention and suck them into the image.

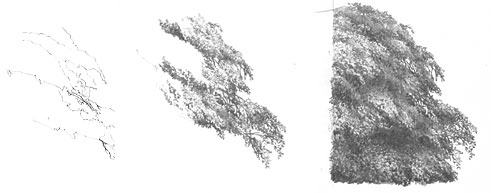

We have only a pointed stylus to work with, so detail tends to dominate our thoughts. Detail can, if used with care, pull the viewer ever deeper into the work. It can educate – invite exploration of what the viewer might recognise but have no real knowledge of – and it can tell our story. That, I think, is what you’re missing – art has to say something! And your language is graphite-based.

In the past I’ve had dealers moan that “If you worked in colour I could sell your work in much greater quantities.” I’d argue that if I worked in colour, it wouldn’t be my work. Despite that, I purchased a few small canvases, an array of paint brushes, and a wide selection of oil paints, so if I felt the urge to paint I could do so immediately. Those paints are in a drawer of the unit that sits by the side of my drawing board… and they’ve been there for over twelve years – unused.

If you feel you need, for commercial purposes, to work in colour then do so, but don’t stop working in your first love, graphite. You may find you sell more drawings on the back of your paintings if your overall sales increase. However, I made a personal decision to stay pure to my love of graphite. It’s true that the available market for drawings is much smaller than for paintings, but conversely the competition is much less too. It’s a niche market that you have to work hard to survive in. That said, if my prints are exhibited in a store, I can guarantee my graphite work will stand out from the plethora of paintings. That’s an advantage you can make use of but only by first refining your craft until you have something of real quality to display.

If colour pays the bills then work in colour. But use your quality time for graphite. Personally, I find nothing beats the direct mind-to-hand-to paper connection of graphite. I think, I draw. One completed section at a time until the overall picture emerges and my story is told. Painting, pastel, coloured pencil are too involved and “mechanical” to suit me – colours to mix, layers to apply…

Now I am wondering if my Graphite drawings are not appealing to the public? What has your feedback been?

My experience is that there’s a small but discerning sector of the public who appreciate graphite drawings. In the same way that some, but not many, appreciate Black & White photography – but most people would accept the argument that classic photography is B&W. We are in the same market. We are not displaying glowing colours that the senses can revel in. No, we, with our palette restricted to just contrast and texture, invite thoughtful appraisal – we provide food for the mind.

Stay faithful to your chosen medium – even if you have to pay the bills with jobbing colour work. And, above all else, draw FOR YOU. While I might make the occasional alteration to a composition to suit my market, I will only do so when it doesn’t adversely affect the story I want to tell or the message that I wish to convey. I draw for myself and always will do. I’m a fine artist and not a commercial artist. Yes, there have been times of despair, just as you are experiencing, but have faith in yourself and your work, and in time others will appreciate it.

Enjoy Ginger Brady’s fine work at: www.GingerBrady.com