Having read my book “Drawing from Line to Life”, Rob emailed me to ask…

I admire your attention to detail without the sacrifice of the ‘drawing’ appeal in your pictures. I was wondering, when drawing trees you mention drawing the internal structure. Are you advocating that when setting out to draw a tree you would draw the internal structure first, then map out the main masses of foliage on the limbs, then go back and erase the bough structure from within the mapped-out areas of foliage masses?

I don’t have any hard and fast rules for myself – I just wing it and do whatever best suggests itself.

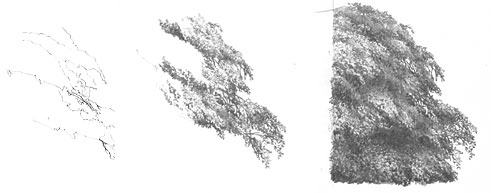

However, one thing is certain – I need to have a three-dimensional idea of what I am about to draw. Establishing the trunk and major boughs gives me an armature to work around. On that skeleton I can then map out (however roughly) the major masses of foliage. If you keep your guidelines light, you probably won’t need to erase them.

You can start with the edges or the centre, but do bear in mind that the central ones will overlap those at the side of the tree. All this helps to reinforce the three-dimensional nature of the structure in your mind but relieves you of the need to work out form and lighting of each element. That said, I often lightly hatch the basic shading required to remind myself later of what I was visualising at the time.

I’m assuming (I hope correctly) that you are referring to midground and background trees. Foreground trees require more planning and tighter detail. Look closely at tress and ask yourself why you know it’s a tree even though, in all probability, you cannot discern actual leaves. Maybe it’s the dappled pattern of light? Perhaps the shadows that describe the three-dimensional nature of each leaf mass? Or, more probably, a combination of the two – and more.

Next decide on the lighting direction and then begin drawing. I prefer to begin with those areas of branch that show through the foliage. as little light enters deep into the tree, and they are seen against a bright sky, they are relatively dark. Establishing one first, in the area that are going to work in, gives you the deepest tone and the white of your paper, of course, supplies the lightest. Now all your intermediate tones will fall into place as you work.

I tend not to shade but to just work in random patterns of lines and scribble; working light with more visible hie remaining in the brightest areas, and overworking the darker areas with more pressure. There’s little conscious thought involved – just watch the tree grow before your eyes.

As each element is three-dimensional, it must obey the laws of light and form – each casting its shadow on the mass below, and having a highlighted top and more shaded bottom.

Take a look at an earlier article of mine (“drawing-trees-and-bushes”), don’t plan too much, keep it free and spontaneous, and you’ll find yourself drawing realistic, organic trees in no time!