Gary posed another question:

Can you offer any advice on how you tackle skies? Skies can sometimes make or break a drawing, especially if you want the focus to be on the scene but need to add some degree of the sky as well – be it understated. Would you apply a cross-hatched technique here and if so, is there a particular method that works well for blending and creating a natural looking sky?

Skies are more important than I once realised! I used to leave the areas white but I soon discovered that adding even a light tone to skies immediately increased the brilliance of highlights within the drawing. In other words, removing all white from a drawing, except where they are intended, forces the viewer’s eye to read highlights as pure, brilliant white.

Applying an overall, smooth tone to skies can present technical problems; there should be a total absence of line and smoothly graduated changes of value. Any marks that don’t conform to Nature immediately reduce your carefully rendered realism to mere “drawing”.

I almost always hold my pencil in a normal “writing” position, but for skies, and other large areas of light tone, I use an underhand grip.

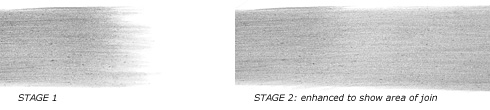

Here I use only the weight of my clutch pencil to apply the tone, and usually with a 2H pencil. Of course, I cannot shade a large area from side to side with a single set of lines, and shading the area in sections leads to two potential problems. First, stopping a line to shade back in the other direction leaves blunt ends. And an overlap of blunt ends when shading adjacent areas will result in a very obvious double layer of graphite.

Over the years I’ve developed a technique to overcome both faults. Try this: practice drawing a line that drops gently onto the paper, continues with the required weight and then is as gently lifted clear. This will produce a line with tapers at both ends. Think of it as drawing an arc – a swing down onto the paper followed by a swing up from it. You can extend such a line at will with no evidence of a join, as a taper over a taper is simply a full strength line.

Once you get a feeling for drawing this way you can begin to shade large areas – with a taper at the end of each line, which you should also stagger to prevent the eye detecting an edge. Each shaded area will now have a feathered edge that you can overlap with adjacent areas – a feathered edge layered over a feathered equates to a solid, matching tone.

Once the area is completely shaded you will need to blend it. Incidentally, blending is a technique I rarely use, except for skies or skin tones. Knowing beforehand that you intend to blend, you can make allowances for this when applying your graphite. That’s why I use the pencil-weight, underhand method, because the graphite sits on the top of the paper and not deep in the tooth. I usually blend very lightly with tissue wrapped around my finger. As the tooth of the paper is still available, I can apply additional layers, if required, to build up the tone.

I don’t customarily produce dark skies or include more than a hint of clouds. For good advice on drawing those I can recommend Diane Wright’s “Drawing Skies” tutorial.

I describe the techniques I’ve mentioned here in much more detail in chapter four of my book “Drawing from Line to Life”.