MANAGEMENT

We previously explored the ways that Negative Drawing can:

- Allow you to concentrate on one texture at a time.

- Draw a structure without reference to it’s three-dimensional shaping.

- Divide any area into a collection of easily-managed elements.

Don’t try to draw many textures at one time. To draw effectively, you must understand the area you are working on, feel its texture, experience its three-dimensionality. We’re creating our own world one step at a time. In order to transmit your mental image of wood through your hand and onto paper, don’t try to draw grass at the same time. If you’re drawing the deep confines of an old wooden crate, you need to experience the deep shadows diluting into mid-tones as they approach the light. You KNOW what it looks like in reality, so don’t dilute your image by suddenly trying to draw the wood around the opening. Concentrate and LIVE one element at a time and you’ll built a reality into your work.

DETAIL and TONE LAYERS

Negative Drawing can be used locally within any area, by using layers to divorce detail from shading. Work logically and with understanding and divide the task into two. Detail and Value. Line and Tone. Detail is often simple to comprehend, especially if viewed as a collection of abstract shapes and unidentifiable negative spaces between them, and line best suits their depiction. On the other hand, tone, which describes the lighting and three-dimensional form of the area, is best suited to an application with a broad, flat pencil lead with a complete absence of line. So why mix the two?

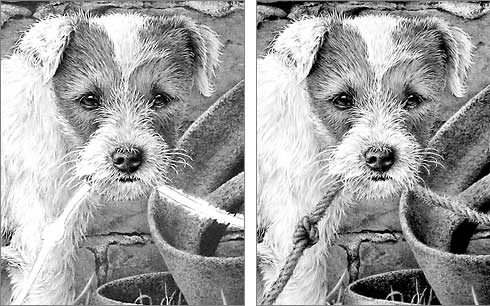

Let’s consider a dog, which has a rough coat of light brown hair, and we’ll work on a small area at a time, perhaps only a half-inch square. This, being manageable, aids our concentration and understanding. The detail layer, formed by line, contains all the cast shadows between the hairs, which negatively create the hairs between them and describe their texture and direction of growth. All tone is omitted so the hairs (created purely by negative drawing) remain virgin white.

Now a tone layer is applied. Some application may be global, describing the overall lighting, shade and three-dimensional form, and other may be local, perhaps enhancing a particular hair or suggesting colour. Further layers may be added as required.

Now, unique to this method, adjustments can be made with Blu-Tack (or a kneadable eraser), as the tone layer can be incrementally removed without affecting the detail layer beneath. I often find that the repeated partial removal and re-application of tone layers produces wonderfully subtle results. And for extra subtlety, try drawing the detail and tone layers and then gently and repeatedly remove both until the merest trace remains. It’s almost impossible to draw with that degree of finesse – something that this system overcomes.

FINALLY…

Let Logic rule: If you reach a point in the area you are drawing where your understanding wanes, leave it. Stop. Move to an adjoining area and work back towards the problem. Your understanding will have greatly increased once you have surrounded the problem area.

Don’t be afraid to draw “too dark”. Blu-Tack or a kneadable eraser will allow you to adjust the intensity later. In the meantime, you have simply split a job into two again: by first establishing the required lines with a weight that helps you see them, then adjusting their tonal values until they meet your expectations.

Concentrate on and draw one texture at a time. “Live” that texture and you will inject life into it.

Don’t be tempted to rush ahead. Doing so may result in inferior drawing. Remind yourself: “My drawing will only be as good as its weakest part!”

Don’t be tempted to leave something if its removal would benefit the drawing – no matter how pleased you are with it. And don’t “showcase” an area of your work that displays your technical prowess. In the words of Pierre Parisienne, “Don’t show me that what you are doing is difficult”. Ultimately it will shout “drawing”, destroy the overall reality, and drag the rest of the study down with it.

“What?” A completed drawing showing areas of subtle white hair produced by drawing over-strong and then adjusting with Blu-Tack. The result has a delicacy that is difficult to achieve by drawing alone.