How do I avoid using copyrighted photos?

Elizabeth asked:

“Do you take your own photos and draw from them? Do you draw from uncopyrighted materials? Or is it entirely from your head? I draw a little, and it’s mostly from horse encyclopedias, old calendars, and free (or not-so-free) stock photos I’ve found on the internet; most pictures I take myself I get frustrated with, but if I want to make any money off of it I can’t legally use someone else’s photography. So I was curious to know how you handled it.”

First, let’s simplify the copyright issue: Unless the originator of your photograph has given permission for it to be used, you are infringing the copyright by copying it – with or without modification. On the other hand, reference photos from a book, the Internet, or any other such source, can be used to provide information and inspiration. Use of such “borrowed” images is perfectly legal if your intention is solely to gain an understanding of, for example, the growth pattern of hair on a bear, the characteristic shape of a particular species of tree, or the texture of a hand-made brick.

If you copy copyright material for your own enjoyment or education, I doubt many photographers will object – but you should always ask first. However, if you use the image for a commercial purpose you’d better be well insured. Like you, the photographer’s income probably comes from his or her work – put yourself in the photographer’s shoes… would you permit it?

When I first began drawing seriously I ran into the same problem that you’re experiencing. Now I always work from my own photos. But I’ve also learned to do without them. I’ll explain…

In the early days I became fixated on detail. I actually believe this is a necessary stage of development that eventually leads to the skill of making rational decisions about what is important to the study and what should be discarded.

I’ve also found that the very best results come not from faithfully reproducing a reference photo but from studying it until I’ve formed a mental three-dimensional image – it’s that image I draw and not the original 2D photographic one.

Photographs are still important suppliers of detail or overall feelings for a subject or texture. For example, when I draw trees, I surround my drawing with suitable photos. A few may provide actual details, some supply a feeling for the textures and internal forms, and all remind me of what I already know.

Once you free yourself from actually copying reference photos you can use whatever you like – book illustrations, stock photos, real life, sketches – because the result takes a little from each but is undeniably YOURS. And that freedom presents one additional bonus – the reliance on memory increases your ability to see and recall everything around you.

The ability to “experience” whatever you are drawing is something I try to teach in my workshops. Once you are physically “living” within the art you are creating, memory, emotion and interpretation are of prime importance and not references.

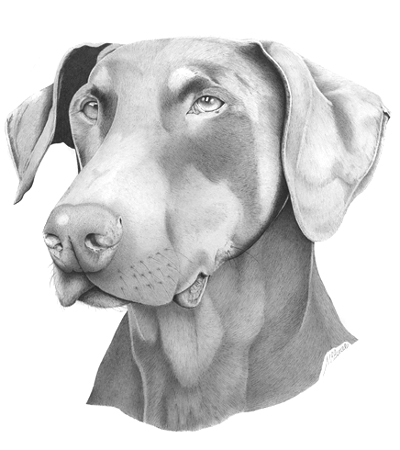

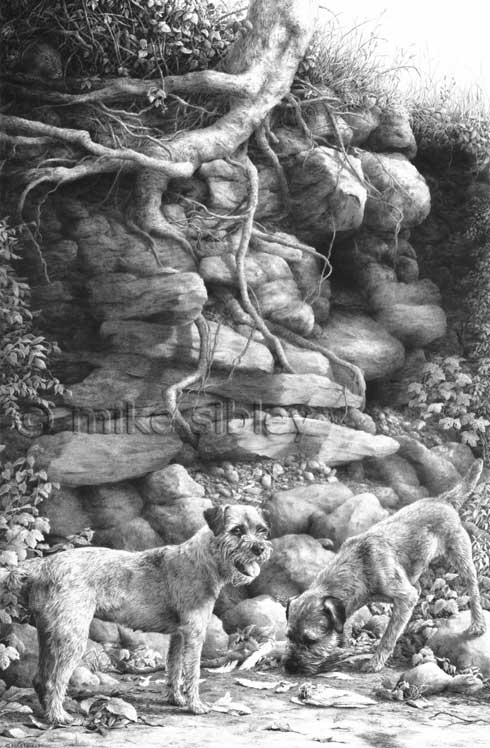

For example, my “Overlooked!” drawing is based on photos that I personally took of Border Terriers – I had perhaps 180 of them, supplying every detail and breed characteristic that I needed.

I had one other single photo – the one that gave rise to the idea – of a tree growing on top of a low bank. The soil had slipped and its roots were fully exposed on one side.

And many years earlier I had photographed a pet wild rabbit (rescued from a hay baler). Those were my references – everything else is entirely imaginary.

Even though the dogs are fairly accurately reproduced from the photos, each part was carefully studied, understood and my mental interpretation drawn.

So, my advice is to gradually cease using photos as the prime source of information. Whenever possible, take your own photos and take MANY. The first shot may be the one you want to use but then zoom in and take more of the detail. Move your position and take more from differing angles – take enough and you’ll be able to pick the subject up as you draw and turn it around to study it from all sides. Many 2D photos will help build a 3D image in your mind. Aim to increase your understanding of the subject and not just to capture its basic image.

You don’t say why you become frustrated with your own photographs. In my case, I’m not a natural photographer and constantly make basic errors. However, if it suits my composition, I can quite readily work from an out-of-focus photograph, because I can rebuild it using detail from all the others I took. If your photos are too dark, load them into Photoshop, or a similar program, and use the Levels facility to display all the previously obscured detail. But that’s a subject to discus on another day…. 🙂