Workshop Plus

WORKSHOPS 2026

- Latest posts:

- Teri Wk1

Teri (Online Beginner)

WEEK 1 EXERCISE 1

I don't usually critique this as it's meant to be a marker against which you can gauge your progress, but it is an excellent feather that doesn't rely on outline or many of the other problems I encounter.

Incidentally, I don't critique here - I download into Affinity (I previously Photoshop) and correct any scanning issues or photography value problems before critiquing, so don't worry if your scans or photos don't exactly match your drawing. If my image noticeably differs from the one you posted I'll post it back again, so you can see what I'm seeing while I critique it.

WEEK 1 EXERCISE 3

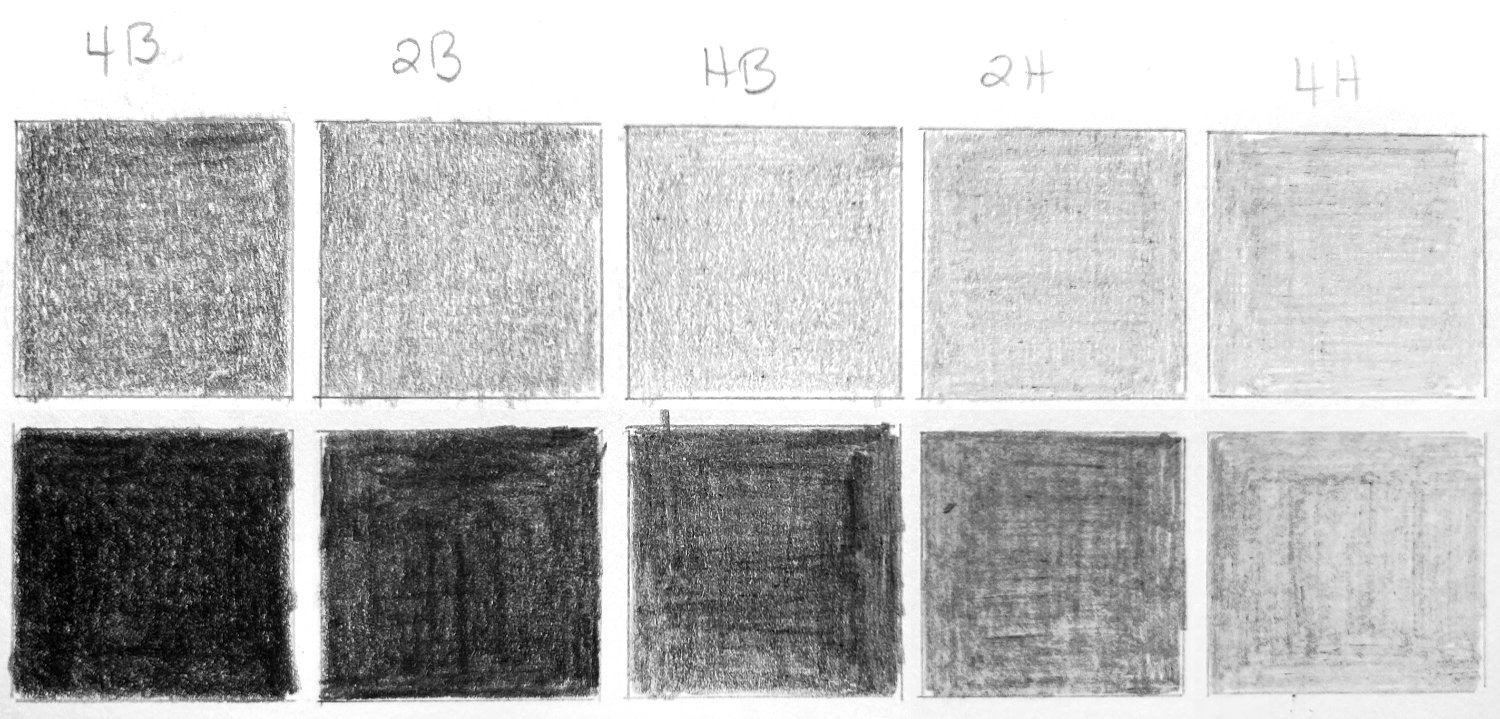

Most of your shading follows two directions, and the lines don't always travel right across a box so, where two layers overlap, they leave a darker band. Don't worry - we'll be covering solutions very soon.

You can shade more evenly by changing the direction of your lines so, if you shade over your existing work using diagonal directions, you will fill some of the lighter areas that you left previously. Or you can shade using tight circles, which is often my preference. In time you'll find the technique that works best for you.

I've adjusted your scan to what I believe (and Affinity suggests) is closer to your original. Your bottom row 4B and 2B blacks appear to be quite dark but they suffer greatly from inconsistent shading. Try working over those boxes again using as much pressure as your lead will stand (probably more than you think it will) with the aim of removing all the white and light content. It's that white content that is severely reducing the impact of your blacks.

The 4B and 2B in particular need to be as black as you can manage, because the more contrast you can generate between your darkest value (tone) and lightest (the white of your paper), the greater will be the range of values available to you. And good solid blacks will add impact to your drawings and help with three-dimensional rendering.

WEEK 1 EXERCISE 4

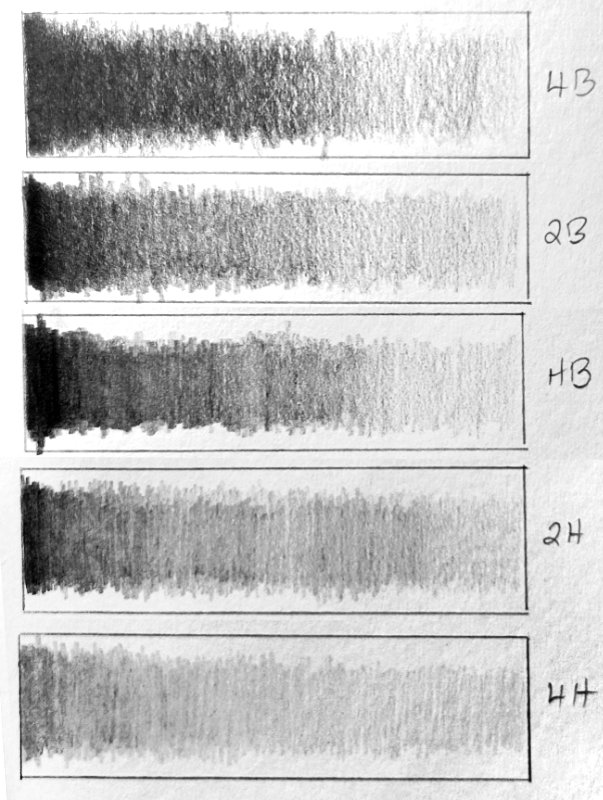

There are visible gaps that need to be removed. Gaps, like the holes in the last exercise, visibly affect the inmtenmsity of the values you inteded. The human mind reds an averafe value.

To smooth out the transition from dark to light, or to remove gaps, you can shade to the right with decreasing pressure and then return to the left, gradually increasing the pressure. That way you can gradually smooth out and fine-tune the overall gradation. If you try that, very slightly alter the angle of your lines on the way back. That will prevent you from drawing directly over an existing line and accidentally darkening it.

When removing gaps, this might help:

When you shade back look at the next GAP and not at what you are drawing. You'll simply watch yourself shade it until it disappears, because the feedback to your hand will be about the gap and its value. Trying to match the line you're drawing to the surrounding values is much more difficult.

If you squint at your boxes you should see that the darkest value of your bottom 4H box can be matched all the way up to 4B. So most pencils can produce many of the values that the other grades can, but the harder grades produce a much smoother finish. That's because the H leads contain a greater ratio of finely-ground clay to graphite.

You can use that to your advantage. For example, you could use a grainy soft grade for drawing a sandy or earthen floor, or a harder smooth grade for drawing shiny metal or smooth glass. The values will be the same but the perceived surface texture is completely different.

Here's some homework for you:

CHISEL POINT

PENCIL TYPES

PENCIL GRADES

FIRST STEPS

I'm going to risk giving you three links from the Intermediate level course, because I think they'll help you to produce a wider range of values, and solid shading, which is important:

DRAWING DARK VALUES

DRAWING MID VALUES

DRAWING LIGHT VALUES

Just don't expect wonderful improvements too soon.

Tutorials

by Mike Sibley