Workshop Plus

ASSISTED ADVANCED: Session 01, 2025

Carolyn (Online Advanced)

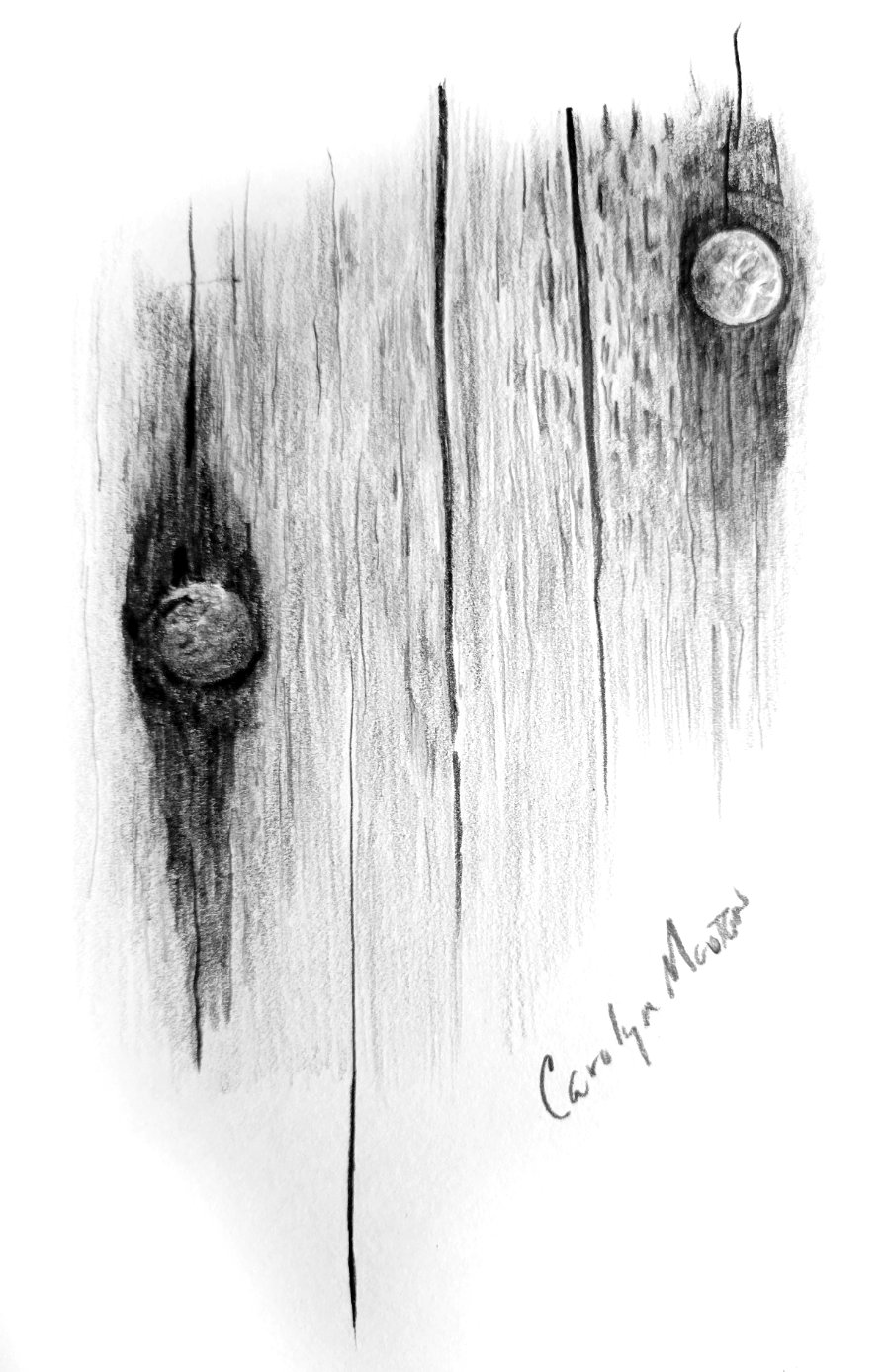

WEEK 1: EXERCISE 1Trying to see the wood fibers and the lighter reflection on the edges of the deep cracks.

Those little touches of highlight running down the sides of the cracks signal that they can ONLY be cracks. Not marks on the surface. We instinctively understand highlights and shadows, and we KNOW those highlights only occur on an actual three-dimensional edge. And to really cement that they are cracks, your terminal tapers are wonderfully long and sharp - exactly as parting and rejoining woodgrain would be.

The wood is nicely understated but still obviously wood. Possibly with little machine-made digs into the surface by the right-hand nail.

The rust staining is correctly darker-toned woodgrain. Again, not marks on the surface. And the nail heads are superb. Both exhibit the sharp detail of rust. The left-hand head appears to be sunk into the wood. Possibly the right-hand one is too, as suggested by that tiny but all-important highlight on the lower edge of the wood. Again, those are signals we subconsciously see and immediately understand.

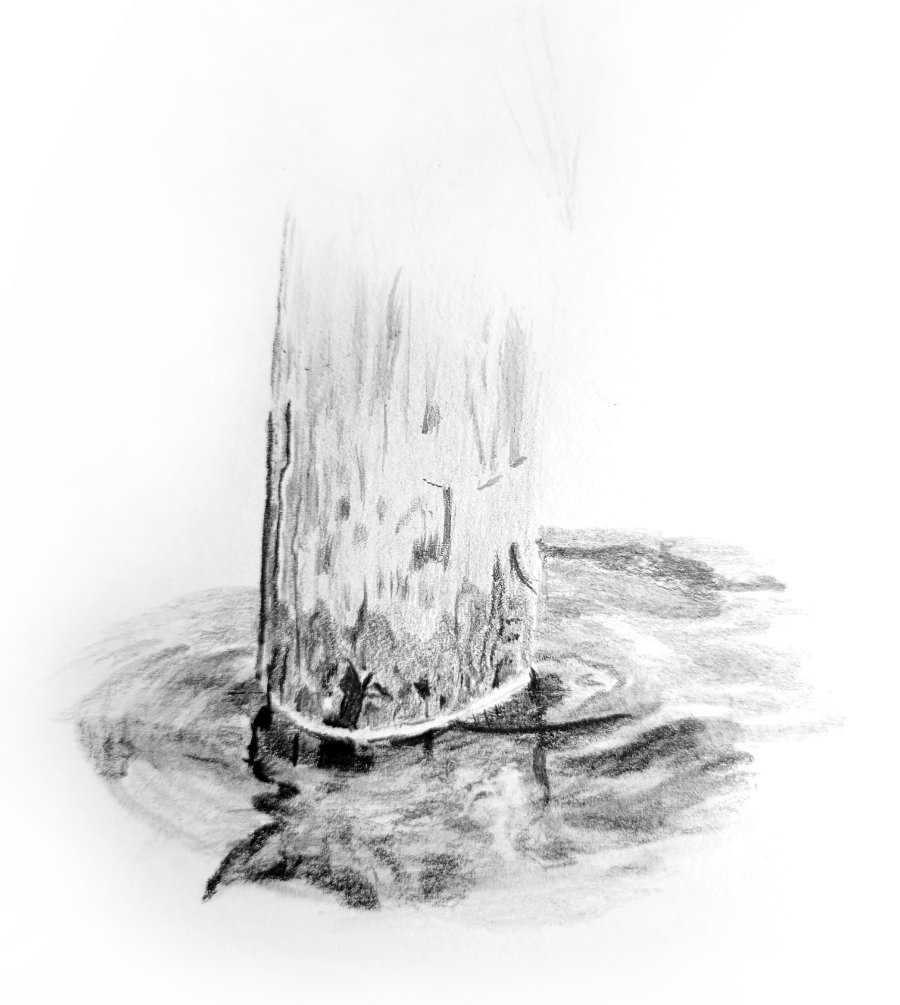

WEEK 1: EXERCISE 2

There isn't a lot of post, so I won't comment on that. But it's reflection in the moving water is super. Well, super up to a point...

That reflected and distorted left-hand edge is all that's needed to tell the story, and it does that very well. However - and I might be splitting hairs here - there are signs of radiating ripples to the left, and those ripples must account for the distortion in the reflection. So far, so good. But then the ripples don't continue within the reflection. That said, it sort of works as it is, but actual ripples would have worked even better.

By that I mean the top and fronts of any ripples face US. They cannot "see" the stumps behind. They can see and reflect the sky, which is why they are light and reflect light towards us. If you enjoy a good Who-done-it (not sure that will translate - detective stories) you'll enjoy drawing, because much of time we're searching for the clues that tell us what something is, or why it looks the way it does. In this case, the ripples would cut across the reflection in light bands. Light, as I said, because they reflect the sky towards us and not the post behind. I hope that makes sense?

Another point just occurred to me: your reflection is correctly darker than the post. I'll state right here that if it needs to be lighter for your drawing to succeed, then that's OK. You can (and I often do) bend the truth. It is not physically and logically correct, but the CLUES are there, so it's completely understandable. If necessary, the human brain is quite adept at making excuses for something not quite conforming to what it expects to see.

Reflections are less contrasty than the object itself. The darks might be similar or even darker, but the highlights will always be more muted. The highlights on the object are caused by light direct from the source being reflected back to you. Highlights in the reflection are not direct from the source, and the water itself, being transparent, will absorb some of the light. That's one reason why I favour cutting pure white ripples across a reflection - it works well because they are too white to be a part of it.

Finally, your ring of surface tension around the pile does its job, although I think it's too broad and would have used a lost-and-found band of brighter, thinner highlights to achieve the same goal. Not that yours is wrong, just different... and, of course, it actually couldn't exist in moving water. But that's back to the mind making excuses for something it understands, even though it knows it shouldn't exist.

WEEK 1: EXERCISE 3

Exercise 3, is trying to be a stainless cat food bowl with a blue rubber base. I found I was trying to copy exactly what I was seeing. On the water, I started trying to just draw the water as I felt it should be, rather than copying it. I found I was more successful that way! So I'm working on not copying!

So, initially, I saw a brushed chrome or aluminium bowl - before I read your description. I now know it also has a rubberised band around the bottom... but that's been partly lost in your drawing.

I find the reflections sufficiently dominant to say "smooth and shiny". Then the soft edges of the reflections modify "shiny surface" to "satin". They also tell me a lot about the three-dimensional form of the bowl. Personally, however, I think your choice of pencil grade or paper (or both) are working against the expected texture. The soft grades used are grainy, which doesn't really describe the surface. Harder grades - or hard layered over soft - would have given a smoother appearance.

Finally, I asked my cat Susie what she thought about the bowl and she said there's only one thing wrong with it... it's empty!

Carolyn (Online Advanced)

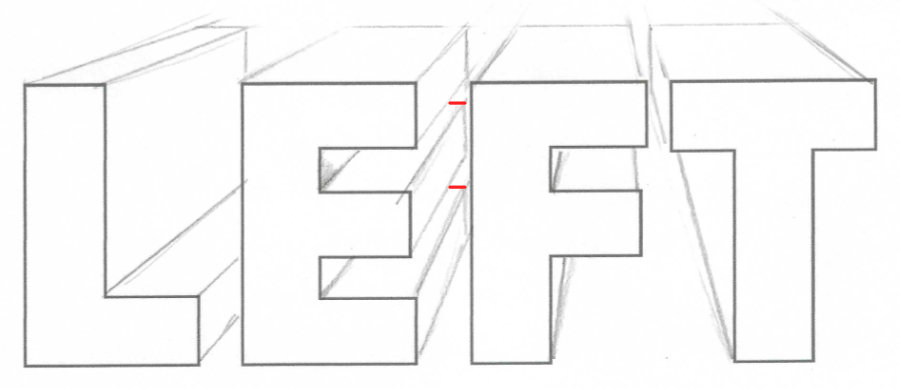

WEEK 2: EXERCISE 1

WEEK 2: EXERCISE 2

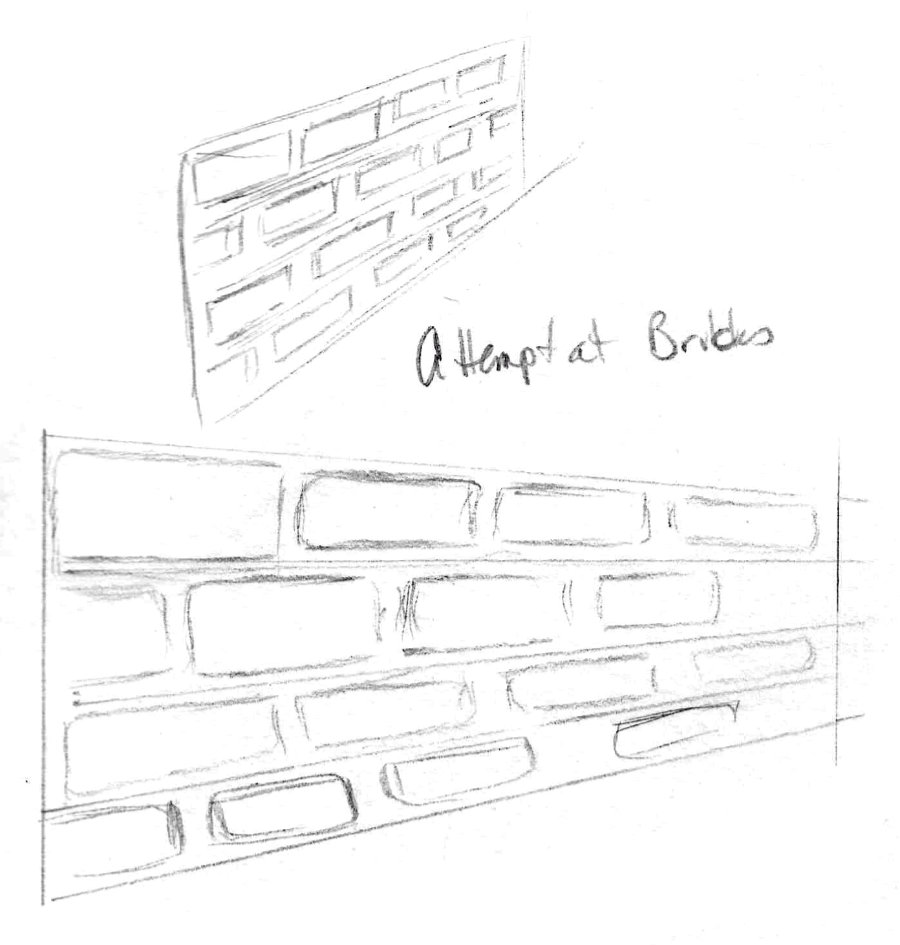

I had trouble with some of these. I do not think I understood the brick exercise, and the use of diagonals. I wasn't sure how/if I should use them for placement of the bricks.

First, the rows in a brick wall are offset by half, so every joint in one row falls under the centre of a brick above. Yours sort of take a bit of a ramble - and the spaces between the bricks (the mortar) are impossibly wide.

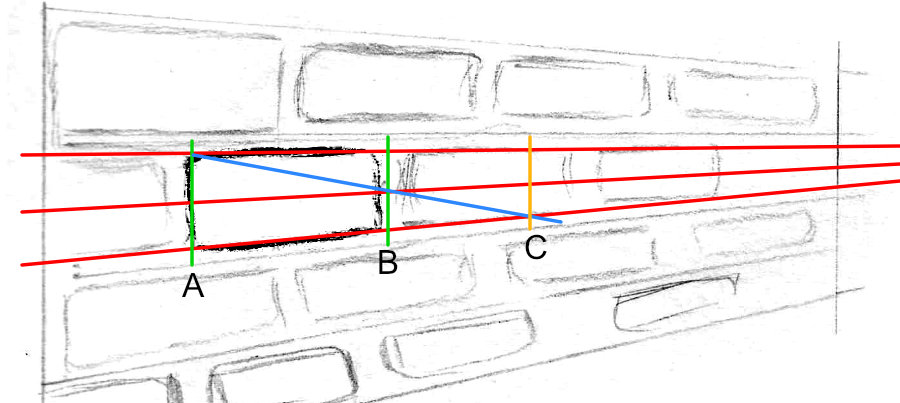

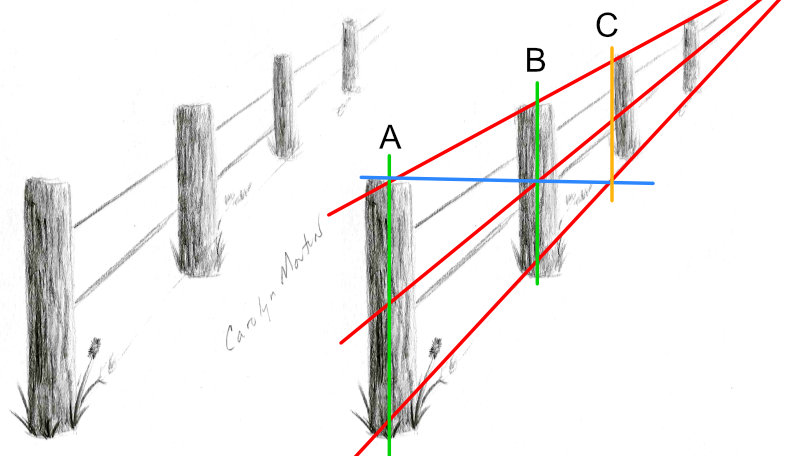

You've already created the perspective for the rows, so that's good. Now you need three convergence lines (orthogonals): one along the top of your first brick, one along the bottom, and a third midway - all emerging from the original vanishing point.

-- Draw a line at one end (A).

-- Draw another line at the other end (B) allowing for the mortar. I ran Line B up the far side of the mortar where I want the next brick to begin

-- Now draw a diagonal line from the top of the brick (where LINE A crosses the top orthogonal) through LINE B where it crosses the central orthogonal.

-- Where the diagonal line meets the bottom orthogonal (LINE C)... that's where the next brick ends. It fits into the space between LINES B and C. Perfectly in proportion and perspective.

Now you can draw the rest by eye. All bricks on the rows above and below move their joints half way along the row you just drew.

Try it, because it's a lesson well worth learning. And once you're really used to it, you can usually just do it all by eye. But you have to understand it first.

WEEK 2: EXERCISE 3

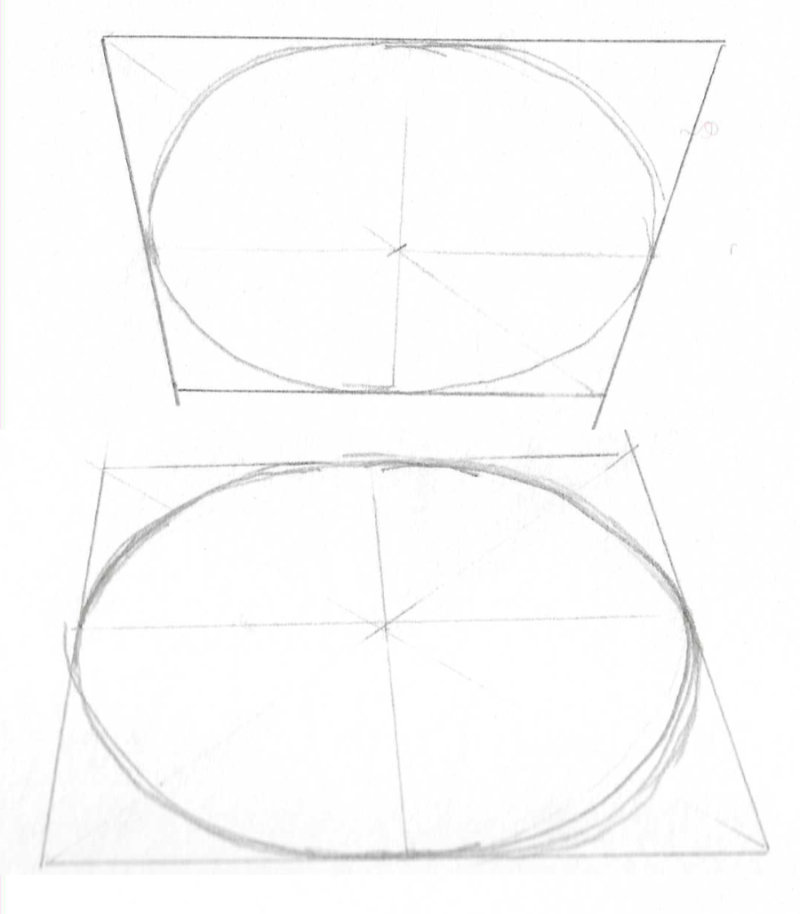

Despite being the result of multiple circuits, this is almost as perfect. Usually, just to make certain, I copy one half, flip it and lay it over the other half.. but I can't do that in this case,because of the multiple tracks. But I'd guess the differences are minimal and my eye would be happy to accept this as a natural ellipse within a drawing.

Try this to train your hand even more: Print out the PDF page with my drawn ellipse on it, place tracing paper over it and then trace it again and again - carefully until your hand begins to learn the gently unfolding or tightening curve. You've already avoided the most common problems - pointed ends and flat sides - so you just need to teach your hand the refinements.

WEEK 2: EXERCISE 4

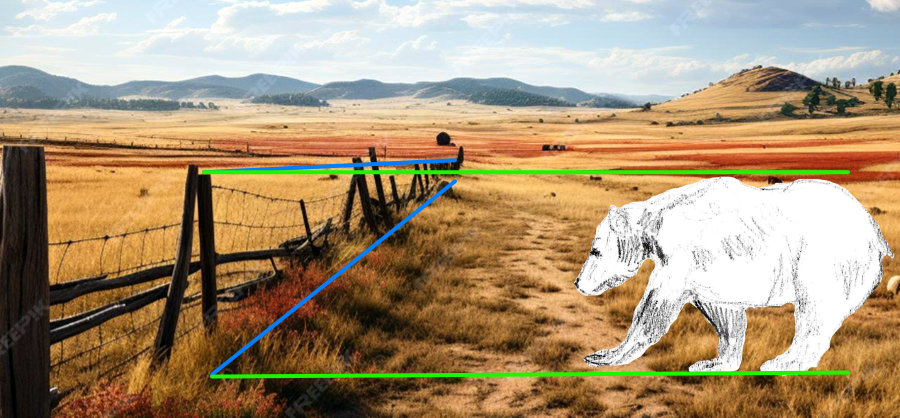

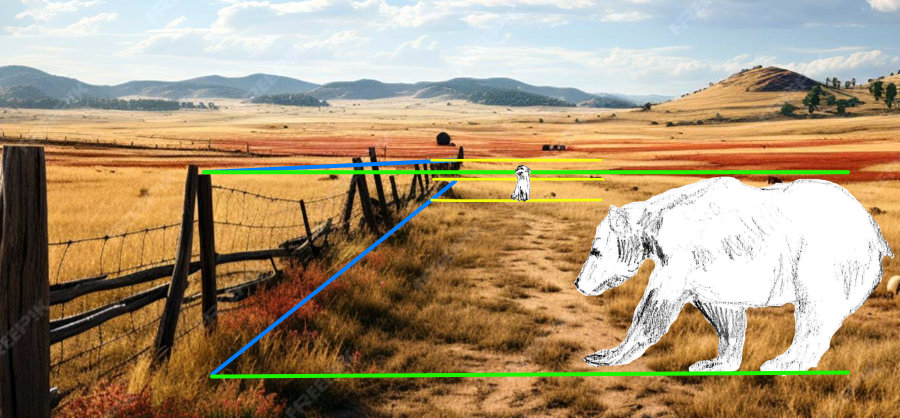

Scene in perspective, part of our pasture fence.

I can see this developing into a drawing with good recession, and a subject where aerial perspective will work very well, especially if you employ a little exaggeration. Don't fear exaggeration. These posts are very similar in value, but sequentially lightening them would reinforce the recession. Imagine a light mist that partially blurs the background. I find that sort of approach often presents an unequivocal scene to the viewer.

Just because I can, I checked the spacing. And I suddenly realised that I'm asking you to accept the "spacing in perspective" method without explaining why it works. My line from A to C finds the TRUE CENTRE in perspective at B.

Now knock in a fence post where you know the centre is. Do you recognise anything? The bricks?

When you pass a line from the top of one post, through the centre of the next post, and continue it down to the baseline, it will mark where the third post has to be placed. You are effectively using the first and middle post to determine the position of the third post.

You can use this method to work out any regular spacing that involves recession.

I hope that makes sense. And, as with most things, the more you are aware of this, and practice it, the easier it becomes to place things in recession by eye.

Carolyn (Online Advanced)

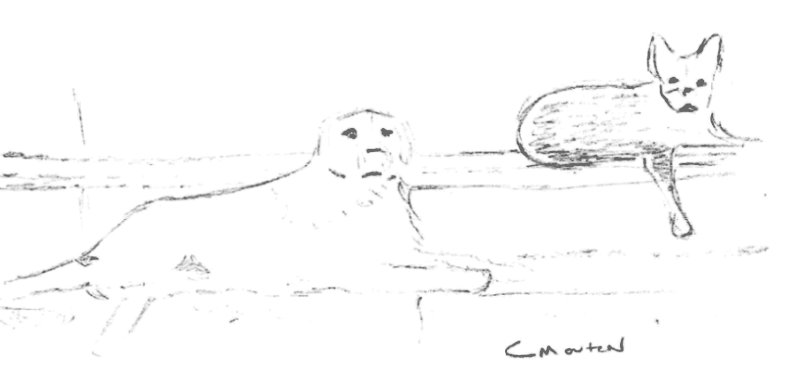

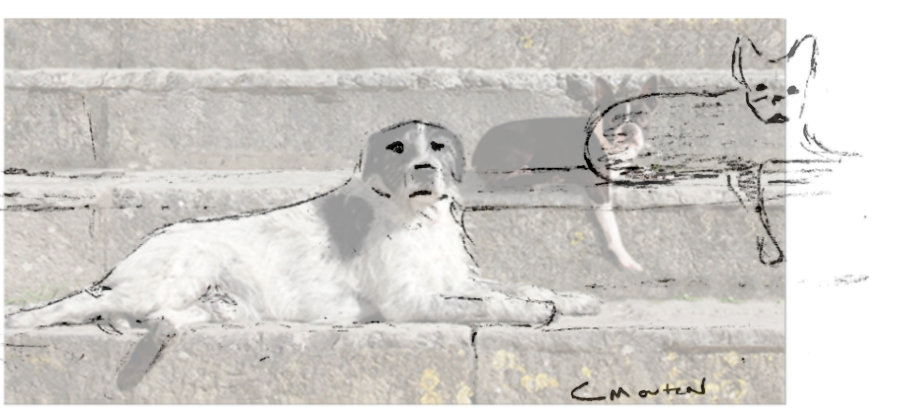

WEEK 3: EXERCISE 1This is a sketch of where I think the Boston Terrier would be compared to the bigger dog. I tried to measure him at a little less the half the height of the other dog and place him on the step.

First, I would have preferred this to have been an image altered in Photoshop or similar. Your drawing is a perfectly acceptable alternative, but it gives me no idea of how you arrived at the smaller dog's size.

Just to check, I resized your drawing to sit on a "correct size" image.

This is what I was hoping to see:

One of the memories that sparked this exercise was, years ago, seeing an artist's work where he'd placed Bull Terriers on a decorative set of stone steps - and the relative sizes were painfully incorrect. We have some expectation of what most things look like - 12" risers are not acceptable. And I suspect the unnaturally high risers resulted from adjusting the tread widths to accommodate his group of dogs.

WEEK 3: EXERCISE 2

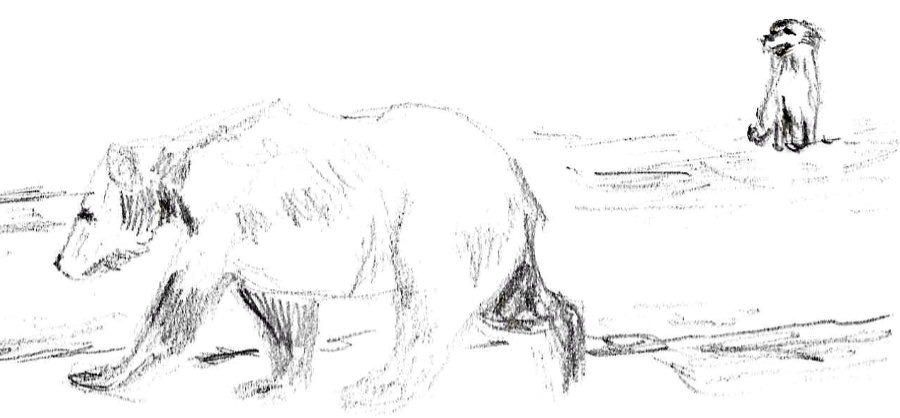

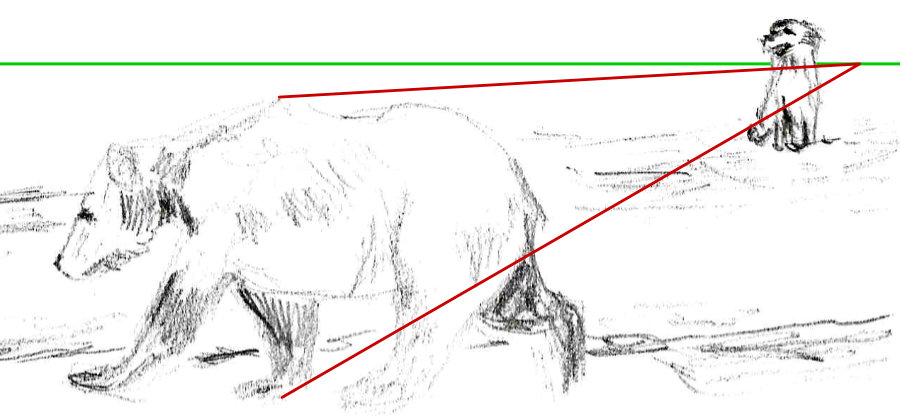

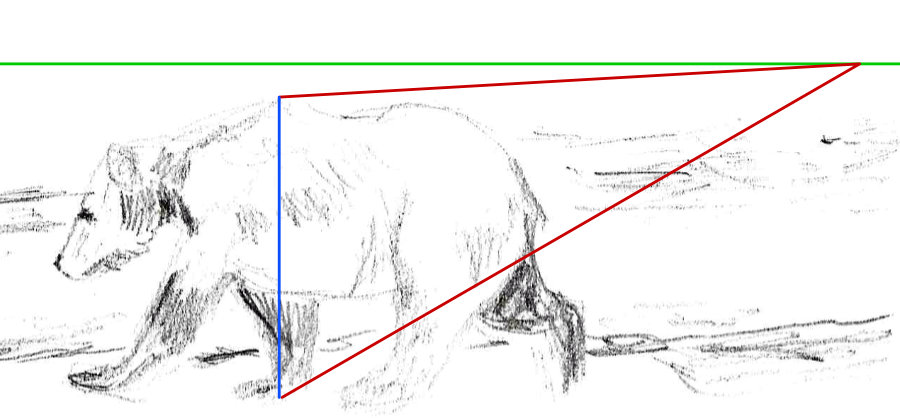

...a photo of a grizzly bear from a zoo, and the right is my 66 lb, 21 inch Australian Shepherd, in the background. I may have made him too small! But it was interesting trying to size him compared to the bear!

Between 3.3 ft and 4.9 ft, so I've decided this one is on the small side at 3.5 feet or 42 inches tall.

Your Shepherd is 21" tall, so it's half the height to the shoulder when standing. So he's half the height of the blue line. Move the blue line (B) to where you'd like to place the dog; and size the dog accordingly. Remembering that the dog is sitting down and only 21" to the shoulder.

So, my yellow lines) are divided in half - because the dog is 21" high - and we can correctly size it to be half the height at its shoulder.

WEEK 3: EXERCISE 2B

The other is a sketch of a polar bear from the zoo, in a metal wagon that my friend has at her house. Don't know how successful that was, but it was interesting to do!

This could be a little stuffed Polar Bear in a child's cart. Or both could be full size. And that difference matters - if only because the cart has to appear to be strong enough to support a HUGE Polar Bear.

That said, your composition works - it's just confusing and doesn't nail anything down.

However, as soon as you throw in something instantly recognisable - such as a jerry can - it suddenly all makes sense size-wise.

Carolyn (Online Advanced)

WEEK 4: EXERCISE 1I hope I understood this assignment correctly! Here are a few attempts of mine to have the subject to the side, as if splitting the drawing in thirds.

These look fine.

WEEK 4: EXERCISE 2

If I start at the dog, he is looking up at the couple and that leads me to them. The man is leaning toward the woman and their bodies are facing to the right side of the painting.

I tend to begin with the dog, too. Both the dog and couple are painted in stronger detail and brighter colours than the muted colours of the background. And they're look directly at me, the viewer, almost asking for an introduction. Interestingly, I also get the impression of superiority, as if they're looking down at us.

Gainsborough would wholeheartedly agree with that, too. I've forgotten the whole story but he detested working for this class of person. They hated the countryside but wanted to display their land, and Gainsborough was deliberately unkind to them in this painting - in ways you'd recognise if you knew the clues to look for, although the clues are probably meaningless is this later age.

Have you thought to ask yourself where the eye-level is? Technically - and based on flimsy evidence - the eye-level would appear to be low. There is very little to go on, because most elements are organic, so I went looking for anything man-made. The bench is the only element available and it's quite clear that we can see the front edge of the seat but not its top. So I'm conjecturing that the seat is exactly at eye-level. If that's true, it would explain my feeling of the couple's superiority. They actually are looking slightly down on us. In fact, If I zoom in to the painting, I'd say that their faces are pointing straight forwards, so they actually are looking down - especially Mr Andrews.

The bench leads my eye from the couple to the landscape. I think the three trees on the right edge stop my eye from going off the page, they seem to make me circle back to the middle of the portrait.

That's interesting move into the scene that rarely occurs with me. As I said, I tend to first notice the dog, or Mr Andrews' leg, because it's the brightest element in the painting, and then to the dog. Both lead up to the couple. My eye then travels up the shotgun to Mr Andrews' tricorn hat. From there, the hat sometimes points me up into the tree, which has branches that send me down the right-hand side. Or I follow the hat to Mrs A, and then follow the bench arm into the right-hand side.

Incidentally, the overhanging branch of the tree prevents your eye from leaving and pushes your view down to the wheat sheaves, which are leaning towards the background, leading you back to the sheep. The row of trees on the left then push back to the rolling hills and up to the clouded sky. Even the clouds seem to curve to the left!

In fact, almost anywhere you look, you can find subtle pointers that steer you around and back to the couple. Except for the quiet area with the deer and the barn, above the dog's head and to the left of Mr Andrews. That area provides a resting place for the viewer, so you're not forced to continually circuit. It's a device I've used myself, and it can work very well.

Lighting around the couple reinforces them as the focal point. Throughout the painting are spots of interest to stop and ponder. The small white flowers by the wheat, the sheep in the field, deer behind the couple on the left. What started out being a basic painting really can become quite fascinating with examination.

The more I study this painting, the more I find. If you look closely at the bottom right-hand corner... there's a cock pheasant sticking its head out from behind the left side of the foreground sheaf of wheat. I'd been looking at this for days before I noticed it.

The more you look into paintings like these, the more you learn about the tricks used to control your route. And, of course, the more you can incorporate into your own work.

Personally, I find the mechanics of composition to be absolutely fascinating, and I have done from way back in my school days. Doc Irwin, my English Literature master, was passionately interested in two subjects - collecting comic books, and advertising design. I can still remember the day that he explained the layout of a toothpaste ad - how the eye was forced to travel a prescribed route and always ended up on the product itself. It was that single explanation that fired my imagination and interest in the subject.

Tutorials

by Mike Sibley